There is widespread interest in measuring healthcare provider attitudes about issues relevant to patient safety (often called safety climate or safety culture). Here we report the psychometric properties, establish benchmarking data, and discuss emerging areas of research with the University of Texas Safety Attitudes Questionnaire.

Six cross-sectional surveys of health care providers (n = 10,843) in 203 clinical areas (including critical care units, operating rooms, inpatient settings, and ambulatory clinics) in three countries (USA, UK, New Zealand). Multilevel factor analyses yielded results at the clinical area level and the respondent nested within clinical area level. We report scale reliability, floor/ceiling effects, item factor loadings, inter-factor correlations, and percentage of respondents who agree with each item and scale.

A six factor model of provider attitudes fit to the data at both the clinical area and respondent nested within clinical area levels. The factors were: Teamwork Climate, Safety Climate, Perceptions of Management, Job Satisfaction, Working Conditions, and Stress Recognition. Scale reliability was 0.9. Provider attitudes varied greatly both within and among organizations. Results are presented to allow benchmarking among organizations and emerging research is discussed.

The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire demonstrated good psychometric properties. Healthcare organizations can use the survey to measure caregiver attitudes about six patient safety-related domains, to compare themselves with other organizations, to prompt interventions to improve safety attitudes and to measure the effectiveness of these interventions.

Experts believe that hhhealthcare quality and safety must be investigated within the framework of systems and contextual factors in which errors and adverse events occur. [1–8] Vincent and colleagues describe several factors that influence clinical practice: organizational factors such as safety climate and morale, work environment factors such as staffing levels and managerial support, team factors such as teamwork and supervision, and staff factors such as overconfidence and being overly self assured. [8]

Healthcare provider attitudes about these and related factors are one component of an organization's safety culture. Influential organizations such as the UK National Health Service, the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the U.S. National Quality Forum are encouraging the measurement of safety culture. This interest derives in part from the experience of other industries (nuclear power, naval aircraft carriers, NASA) that are known for their ability to reliably deal with risky processes. [9]

Despite considerable interest, there is limited psychometric and benchmarking data available for the surveys designed to measure these attitudes [10–13]. The aims of this paper are to present our experience with the University of Texas Safety Attitudes Questionnaire. We describe the survey's background, psychometric characteristics, provide benchmarking data, discuss how the survey can be used, and note emerging areas of research.

Safety culture has been be defined as "the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organization's health and safety management [13]." The SAQ elicits a snapshot of the safety culture through surveys of frontline worker perceptions. When using questionnaires to study group-level perceptions, the most appropriate term to use is climate (e.g., safety climate, or teamwork climate). Climates are more readily measurable aspects of safety culture (perceptions are part of both definitions) but surveys are generally not capable of measuring all other aspects of culture like behavior, values, and competencies. However, readers should be aware that some papers, organizations, and opinion leaders use the terms climate and culture interchangeably. We use the term climate where some may expect to see the phrase culture of patient safety.

Here we use clinical areas (a.k.a., work units, patient care areas, nursing units) as the group-level of interest. By testing the psychometrics of the SAQ at the individual level and the clinical area level, we can test the appropriateness of conceptualizing patient safety issues at the clinical area level, because clinical areas are generally associated with managers, geographical locations, and specific clinical and operational outcomes.

The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) is a refinement of the Intensive Care Unit Management Attitudes Questionnaire, [14, 15] which was derived from a questionnaire widely used in commercial aviation, the Flight Management Attitudes Questionnaire (FMAQ). [16, 17] The FMAQ was created after researchers found that most airline accidents were due to breakdowns in interpersonal aspects of crew performance such as teamwork, speaking up, leadership, communication, and collaborative decision making. The FMAQ measures crew member attitudes about these topics.

Because 25% of the FMAQ items demonstrated utility in medical settings in terms of the subject covered and factor loadings, they were retained on the SAQ, The new SAQ items were generated by discussions with healthcare providers and subject matter experts. In addition, we relied upon two conceptual models to decide which items to include: Vincent's framework for analyzing risk and safety [8] and Donabedian's conceptual model for assessing quality [18] This generated a pool of over 100 new items covering four themes: safety climate, teamwork climate, stress recognition, and organizational climate. Items were evaluated through pilot testing and exploratory factor analyses. This phase of survey development consistently yielded 6 factor-analytically derived attitudinal domains containing 40 items from the survey (two, three, four, and five factor structures were less robust). Three of the targeted themes, safety climate, teamwork climate, and stress recognition, emerged as factors. In particular, safety climate and stress recognition are conceptually quite similar to their counterparts in aviation. [19] The fourth targeted theme, organizational climate, consistently emerged as three distinct but related factors, perceptions of management, working conditions, and job satisfaction. Organizational climate plays a decisive role in setting the preconditions for success or failure in managing risks [3, 4, 20] , and we therefore retained these three factors as part of safety attitude assessment. An additional 20 items were retained because they were deemed interesting and valuable to the unit managers and senior hospital leadership to whom we reported the results of our pilot studies.

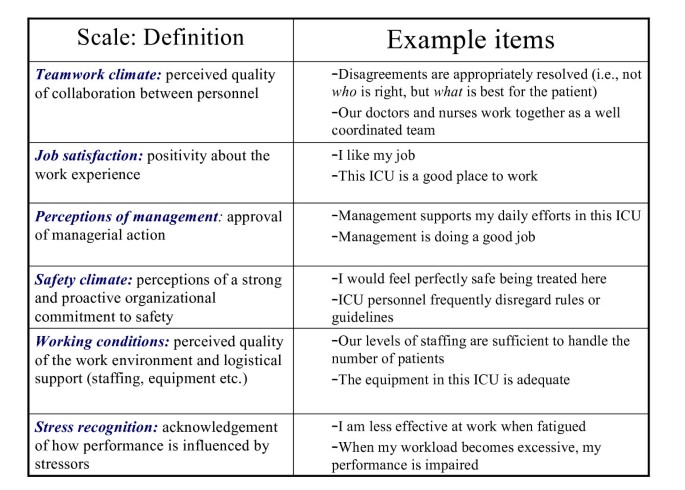

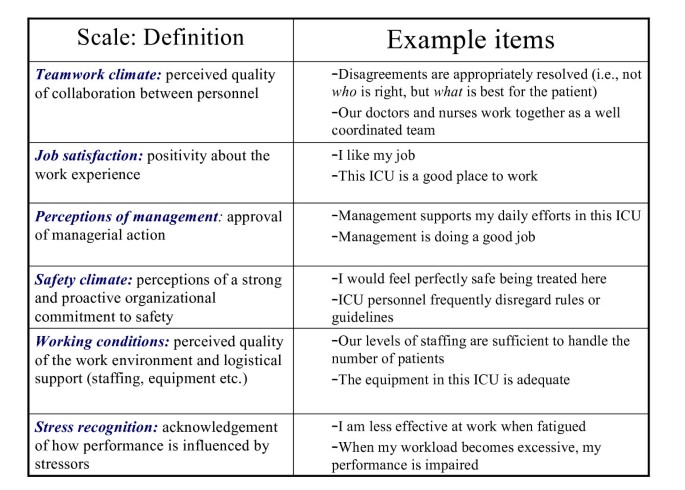

The SAQ has been adapted for use in intensive care units (ICU) [15, 21] , operating rooms (OR), general inpatient settings (medical ward, surgical ward, etc.), and ambulatory clinics. For each version of the SAQ, item content is the same, with minor modifications to reflect the clinical area. For example, "In this ICU, it is difficult to discuss mistakes," vs. "In the ORs here, it is difficult to discuss mistakes." The SAQ elicits caregiver attitudes through the 6 factor analytically derived climate scales: teamwork climate; safety climate; job satisfaction; perceptions of management; working conditions; and stress recognition (Figure 1).

The SAQ is a single page (double sided) questionnaire with 60 items and demographics information (age, sex, experience, and nationality). The questionnaire takes approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete. Each of the 60 items is answered using a five-point Likert scale (Disagree Strongly, Disagree Slightly, Neutral, Agree Slightly, Agree Strongly). Some items are negatively worded. There is also an open-ended section for comments: "What are your top three recommendations for improving patient safety in this clinical area?" Each version of the SAQ in the current study includes a "Collaboration and Communication" section, where respondents are asked to indicate the quality of collaboration and communication they have experienced with each of the types of providers in their clinical area (e.g., Staff Surgeons, Surgical Residents, Staff Anesthesiologists, OR Nurses, etc.) using a five-point Likert scale (Very Low, Low, Adequate, High, Very High).

Early survey development, pilot studies, and exploratory factor analyses were conducted in four USA critical care sites. [14, 15] This work lead to a six-factor solution using 40 of the 60 items, [21] and set the stage for the subsequent survey administrations reported in the current study. The data presented here came from six administrations (Table 1) of the SAQ between 2000 and 2003, totalling 203 sites (in the discussion we briefly note results of more recent survey administrations led by other investigators). We conducted further pilot testing of the SAQ for the United Kingdom and New Zealand, but aside from simple translations (e.g., USA Attendings and Residents became UK Consultants and Registrars, respectively) there were no substantial revisions. The first non-pilot version of the SAQ was administered in 106 United Kingdom (UK) ICUs. The second administration took place in 20 New Zealand (NZ) ICUs. The subsequent administrations occurred in the following sequence: 11 USA Inpatient settings, 2 USA OR settings, 11 USA Ambulatory Clinics, and 53 USA ICUs.

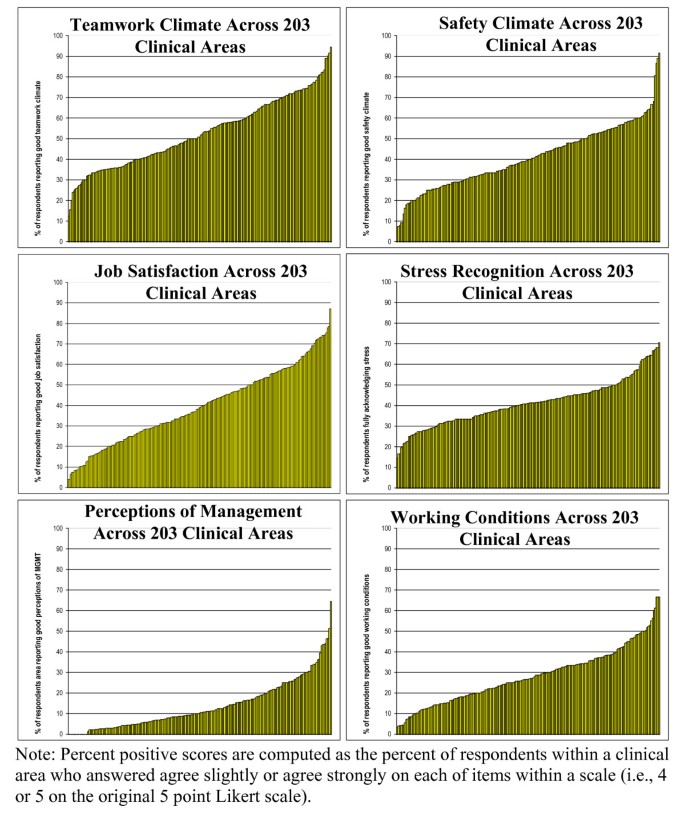

The SAQ is a psychometrically sound instrument for assessing six safety-related climate domains by systematically eliciting input from front-line caregivers. The SAQ can be used to meet the increasing demand for safety climate (often called safety culture) assessment at the clinical area level. For comparison purposes, those interested may use the 203 clinical areas reported here, as they demonstrated substantial variability in teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, stress recognition and working conditions. We found substantial variability in teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, stress recognition and working conditions. The item descriptives (Table 3), together with the percent positive distributions (Figure 2), and the administration-level descriptives (Table 1 and Table 2), serve as benchmarking data for the SAQ. Examination of Table 4 shows that the 6 factors have lower correlations at the clinical area level than at the individual respondent level, indicating that the 6 factors are more diagnostic (share less variance with each other) when used at the clinical area level.

For example, institutions like the Memorial Hermann Healthcare System, Ascension Health, and Johns Hopkins Hospital use the SAQ to assess safety climate hospital-wide, (at the clinical area level) annually. These clinical areas benchmark their climate against other units in their institutions and against themselves. Strengths and weaknesses in a given clinical area (relative to comparison data) can be identified and appropriate interventions undertaken. For example, a poor teamwork climate would suggest collaborative rounds, [36] whereas a poor safety climate would suggest Leadership WalkRounds [37] or a Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program [38]. When used in a pre-intervention/post-intervention methodology, the SAQ factors have demonstrated sensitivity to quality improvement interventions at Kaiser Permanente [39] and recent evidence from Johns Hopkins Hospital demonstrates that climate can be targeted and improved. These improvements are associated with reductions in medication errors and with shorter lengths of stay [38]. Recent data from the Keystone ICU collaborative of critical care units in Michigan demonstrated that critical care units with the highest scores on SAQ factors had the lowest subsequent blood-stream infection rates (personal communication: Peter Pronovost, June 2005).

Such examples of how the SAQ is used help provide information about convergent validity and construct validity, two important psychometric characteristics not analyzed in this study. For example, SAQ climate scores of critical care personnel are correlated with James Reason's Checklist for Assessing Institutional Resilience (CAIR) scores of middle-level managers in the same institutions. [40] In other words, an independent assessment of safety climate using a different instrument produced the expected convergent results. Also, analyses of the SAQ open ended comments for "What are your top three recommendations for improving patient safety in this clinical area?" provides a form of convergent validity when the content of comments is linked to the SAQ factor scores. For example, ICUs with poor teamwork climate scores had significantly more respondent comments regarding the need to improve communication, relative to ICUs with high teamwork climate scores. [41] Similarly, ICUs with high stress recognition scores made more recommendations regarding the need for increased staffing levels relative to low stress recognition ICUs (i.e., respondents who acknowledge the effects of stress on their performance were much more likely to identify the need for improved staffing levels).

Our results indicate that researchers should consider hospitals comprised of clinical areas to resemble corporations comprised of organizations, because the clinical areas appear to resemble what are typically considered organization-like unique climates. The multi-level model demonstrated that there is more variability between clinical areas than within clinical areas. In other words, context of care assessments appear to be more robust, meaningful, and interpretable at the clinical area level. Climate at the clinical area level is important as many clinical and operational outcomes are tracked at the clinical area level (e.g., catheter related blood stream infections in intensive care units), and it is easier to target clinical area level improvements than hospital wide improvements. We see the focus on clinical area level climate as a way to acknowledge the complexity of the systems in which caregivers work, rather than assuming monolithic hospital climates that lack diagnosticity of clinical area level issues.

The SAQ differs from other medical safety climate or "culture" surveys [10–13] in four respects: first, the SAQ has been more widely used for a longer period of time, so there is benchmarking data available and many of the challenges of longitudinal assessment have been encountered and addressed; second, a larger amount of psychometric data is available for the SAQ; and third, the SAQ maintains continuity with its predecessor (the FMAQ) – a traditional human factors survey with a 20 year history in aviation. [16, 17] The availability of benchmarking data in the public domain enables organizations to evaluate their own climate data. Also, preserving item continuity with other high-reliability industries allows for comparisons between professions [14] , and assists with the search for universal human factors issues across professions.

The SAQ demonstrates generally good psychometric properties, though a number of the factor loadings at the clinical area level were smaller in magnitude than the corresponding factor loadings at the individual level. Not surprisingly, the standardized root mean residual (SRMR) model fit statistic at the clinical area level was larger than desirable, indicating that further scale refinement could result in stronger factor loadings and a better fitting model at the clinical area level without sacrificing integrity of measurement at the individual caregiver level. As noted above, a number of studies have linked SAQ factor scores to important clinical outcomes [38] and other instruments that are used in healthcare. [40] Nonetheless, further research on the relationship between SAQ factors and other variables such as staff turnover, patient morbidity, length of stay, and errors is needed.

Lastly, due to the limited scope of this study, it was not possible to assess factor structure invariance across countries, job categories of respondents, or other stratification variables. At a minimum, we demonstrated the validity of the SAQ in a large heterogeneous sample made up of many different healthcare provider types, clinical areas of various acuity levels, countries of origin, hospital types, gender, experience level, etc., in hopes that the results will generalize to a wide variety of healthcare providers.

It is possible to reliably and meaningfully measure caregiver attitudes and perceptions relevant to the safety of healthcare. Use of the SAQ to assess climate in clinical areas will allow valid comparisons between hospitals, patient care areas, and types of caregivers, and tracking of change over time. We can and should do more to tap into the wisdom and perspective of the frontline caregivers regarding the contexts in which they deliver care. Versions of the SAQ, as well as the SAQ Users Manual and additional benchmarking data can be downloaded from our website. [42]

Safety Attitudes Questionnaire